Made in the USA

By Alben Osaki

I’m an Asian American. My dad was Japanese and my mom is Korean. But growing up, I never really thought of myself that way. I just saw myself as “American.” See, I grew up in what’s probably one of the most diverse states in the country, Hawaiʻi. I grew up with a lot of people around me who, to be frank, also looked like me. And a lot of people who didn’t.

The author and one of his childhood best friends, Le’a (left), cooking something in elementary school.

That’s not to say that I grew up under a rock. I was at the very least vaguely aware that Hawaiʻi was unique in that way. But it was rarely something I actively thought about. English is my native language and the only one I speak fluently. I loved playing baseball with my friends growing up. I served in the US Navy for a number of years. As far as I was concerned, I was as American as apple pie and Budweiser.

As I got older and lived in other parts of the country, however, my racial identity started to slowly creep into my consciousness more and more often. And it all came to a head about a year or so ago.

The past year and a half has been insane for everybody. The world shut down. People lost jobs. Folks died. And it felt like it all happened so quickly. One second everything is seemingly normal. Then suddenly, Disneyland shut down. When Disneyland shuts down, you know shit’s hit the fan. Literally a few hours later, my boss tells me and all of my coworkers that we’re being furloughed for the foreseeable future. It felt like, outside of the toilet paper industry, everybody was losing their jobs. And then people started getting sick. Then they started dying. All because of this crazy virus that originated out of China.

The author in Camp 4, Yosemite National Park.

It started to bring the crazy out of people. And I think I can understand why, not that I necessarily agree with it. Being cooped up at home, with the future in so much doubt, everyone had to cope with the “China virus”, as some people called it, in their own ways.

One day, I was sitting outside of a laundromat, minding my own business and messing around on my phone like any normal human, waiting for my load of laundry to dry. As I was catching up on my daily Reddit intake, this old white guy walked up to me and stood in front of me, just a few feet away. He stands there for a few awkward seconds and just kind of… stares. Finally, he breaks the silence, “Hey,” he says to me. I look up at him. “You speak English?” he asks gruffly.

I was so caught off guard by his question, it took me a full beat or two for me to process what he was asking. “Uh… yeah,” I replied, dumbfounded.

He nods his head, “Oh, good.” he says, and turns around and walks away. As he steps off in the other direction, my face was probably the literal expression of the mind-blown emoji. Did he really just ask me that? What would he have done if I didn’t speak English? And why did it matter?

Since sharing that story, a lot of my other Asian American friends have come out of the woodwork with similar stories. One friend, Casey, told me how he had an Uber driver call him and ask if he was Asian. When he replied yes, his ride was canceled.

My mom, who still lives in Hawaiʻi, calls me worried all the time, like any normal mom would I suppose. Except she’s mostly worried about me getting harassed because of my race. Worried more than my mom should be worried because her American son is living in South Texas.

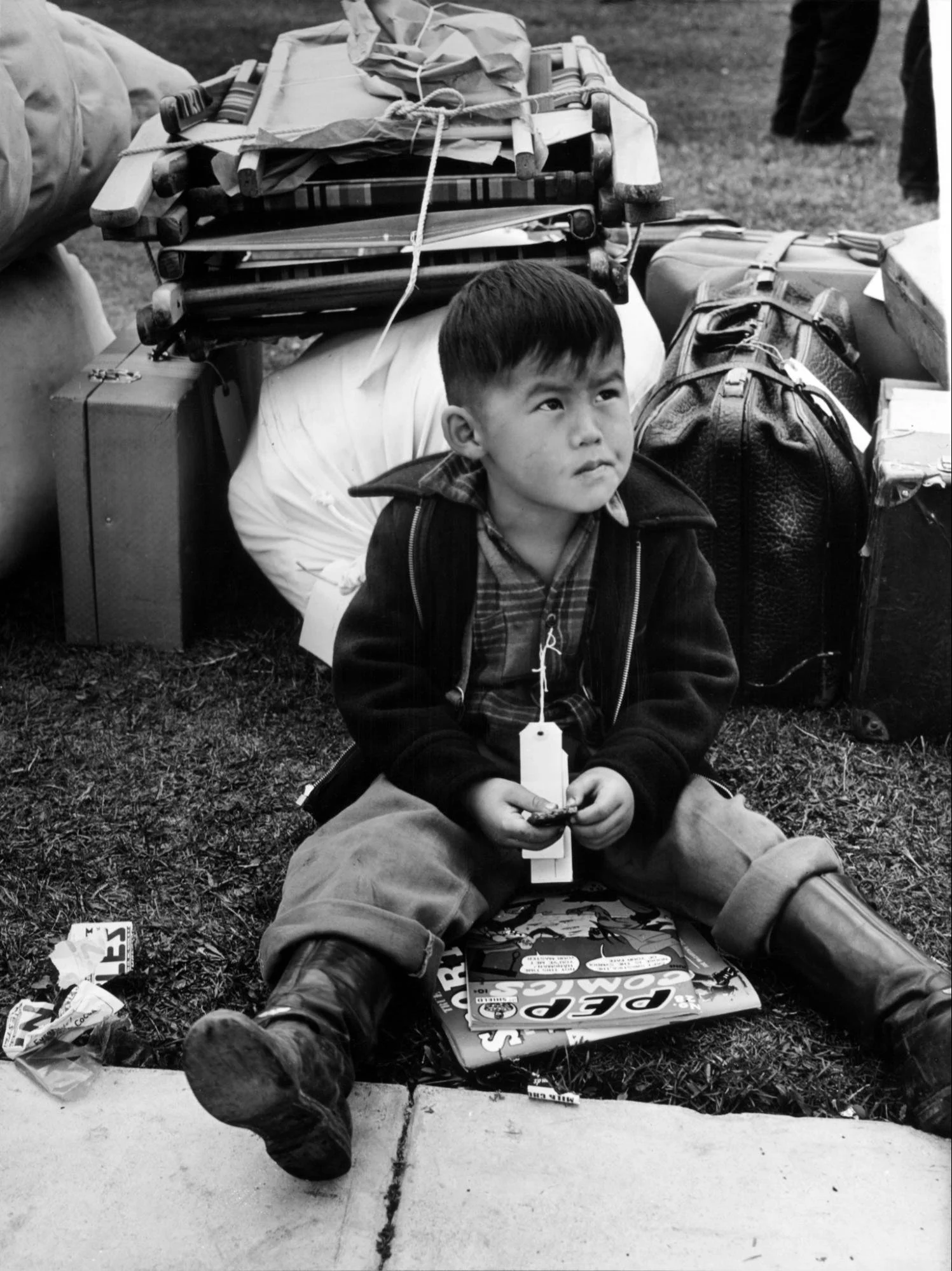

Salinas, California, 1942. A Japanese child is “tagged for evacuation” to a concentration camp. During the Second World War, about 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry were incarcerated and sent to concentration camps in the US because of their race. Credit: Russell Lee, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

I work at a news station now, as of July. During one of our weekly Zoom meetings, we were talking about what stories we should air on Veterans Day. “We could re-air that interview we did with that World War II veteran we did this past Memorial Day.” someone suggested.

“What was the interview about?” I asked. This interview had occurred before I started working there.

“He’s a Pearl Harbor survivor. He talked about the attack and his time serving during the war.” there was a short pause. “We’re gonna need to edit the interview though. He did say ‘Japs’ a whole lot. Product of his time.”

Cue the mind-blown emoji again.

Considering not just the past year and a half, but also the treatment of Japanese Americans by the US government during World War II, this seemed incredibly tone-deaf.

As calmly as I could, I said, “We don’t need to air that interview. I get that it’s a product of the time, but it’s not that time anymore.”

To everyone’s credit, they all agreed.

Sergeant Goichi Suehiro with the then-segregated 442nd Regimental Combat Team watches for German units in France during World War II. The 442nd was composed of Japanese American volunteers, many from US concentration camps. While fighting in Europe against Nazi Germany, their families were still being held by the United States in those concentration camps. The 442nd is the most decorated US military unit in history, earning more than 18,000 awards, including 21 Medal of Honors, 560 Silver Stars, 4,000 Bronze Stars, and more than 4,000 Purple Hearts. Photo Courtesy of U.S. Army, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The author along with the rest of the USS Chosin’s Visit, Board, Search, and Seizure team, deployed to the Horn of Africa.

I don’t want to speak for others, but I know personally, I tend to marginalize my own experiences.

“Oh, that guy was just asking if I spoke English. It’s not like he tried to beat me or anything. I shouldn’t complain.”

The problem is, when I marginalize my own experiences, it marginalizes everyone else’s experiences too. The plain fact of the matter is, bad is bad; racist is racist.

Just because it’s not *as* bad or *as* racist, doesn’t make it any more okay.

I realize that it’s not completely rational, but now I sometimes think twice before I leave my house.

I subconsciously make it more of a point to speak with everyone I meet in my perfect, public school-educated English. I sometimes wear my Navy ball cap. I’m hyper-aware of people’s interactions with me. Did they say hi to someone else but ignore me? Did they make eye contact with me? What was the tone of their voice? I try to outwardly appear more “American;” to prove my “American-ness.” Something all too familiar to many Asian immigrants throughout the history of the United States.

But at the end of the day, I am Asian. And I am American. And it should feel like I belong. But to be honest, sometimes it doesn’t.

And that’s a damn shame.

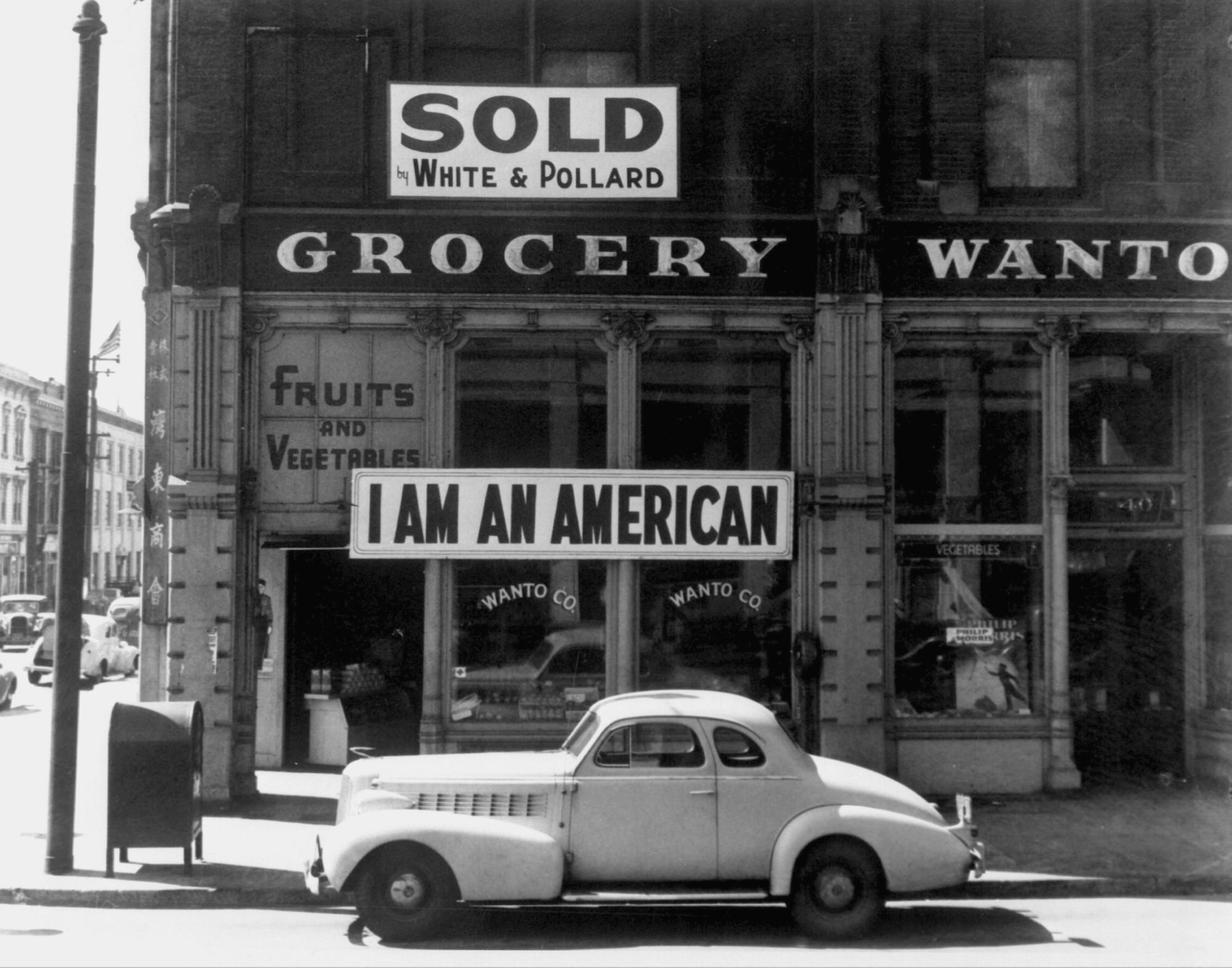

A Japanese American citizen unfurled this banner in Oakland, California the day after the Japanese attack of Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941. This photograph was taken in March 1942, just prior to the man's internment and relocation to a concentration camp. Credit: Dorothea Lange, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Alben Osaki is a photojournalist and filmmaker residing in South Texas, with a focus on the outdoors.