Omnipotent Heroics

By Owen Clarke

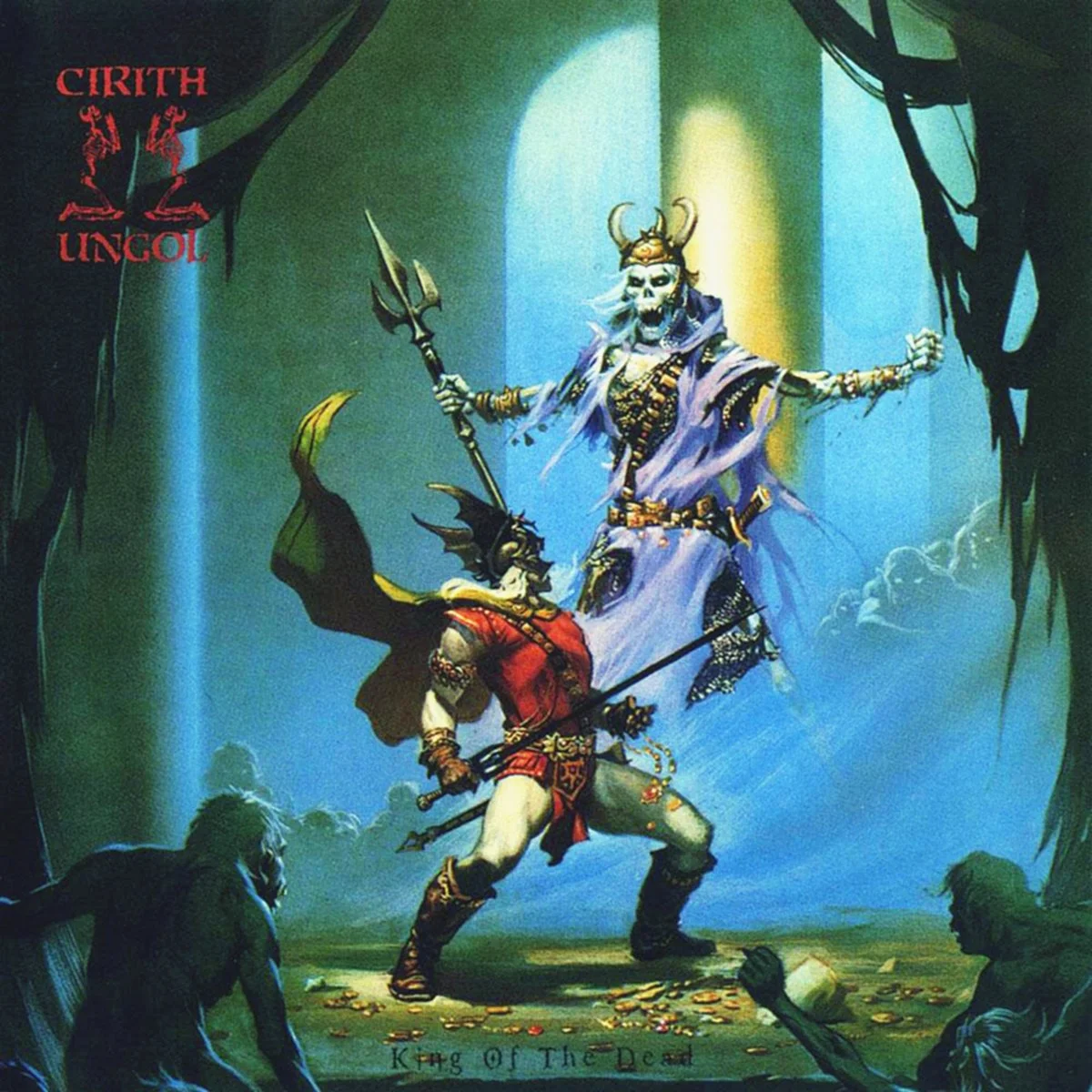

“I can tell from the album art if you’re going to like the record or not,” my girlfriend told me over a beer on our couch last weekend. She nodded towards the Cirith Ungol poster on the wall behind us.

Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian, a typical sword and sorcery hero, after a long day’s work.

“It’s simple. It’s always the same. It’s gonna have a big muscular guy with a sword and long hair, and he’s always fighting skeletons or monsters or whatever, and sometimes there’s a naked girl, and lots of fire. It’s the same way with the books you read, and the movies you watch,” she added, laughing.

I couldn’t do anything but shrug and laugh back, because well… She was right.

While I hope my tastes are broader than muscular men hacking down monsters, I have developed a predilection towards sword and sorcery content, towards strong-armed protagonists with seemingly boundless power, standing alone against villainy.

I’ve always had a soft spot for fantasy, but the older I get, the pulpier it is the more attracted I am. The bigger the biceps, the heavier the axe, the longer the odds, the more I enjoy it.

Of course, the idea that the media we find appealing, or more aptly, the heroes we idolize, tend to change as we ourselves change and grow is no secret. Nor is it a stretch to think that some parallel can be drawn between the person we wish we were and the fantasy heroes we love to read about.

What confuses me is why I seem to be devolving in taste the older (and hopefully more mature) I get. One-dimensional sword and sorcery heroes like Conan the Barbarian and Kull of Atlantis are the sort you’re supposed to be drawn to as a prepubescent boy or a middle-aged incel. I used to be repelled by these sorts of knuckle-dragging protagonists with unlimited power. I found their stories dull, one-sided, and formulaic. Most people do.

You always know what’s going to happen. They’re going to be a head taller than everyone else in the story, they’re going to kill everyone that stands in their way, they’re going to find some treasure, save a woman, and ride off into the sunset.

The protagonists are omnipotent. They struggle against long odds, but they always succeed in the end.

What is there to appreciate about omnipotence? I’m not sure.

⸻

On power and fantasy, prolific American author Stephen King presents an enlightening take in Danse Macabre (1981).

All fantasy fiction is essentially about the concept of power; great fantasy fiction is about people who find it at great cost or lose it tragically; mediocre fantasy fiction is about people who have it and never lose it but simply wield it.

Mediocre fantasy fiction generally appeals to people who feel a decided shortage of power in their own lives and obtain a vicarious shot of it by reading stories of strong-thewed barbarians whose extraordinary prowess at fighting is only excelled by their extraordinary prowess at fucking; in these stories, we are apt to encounter a seven-foot-tall hero fighting his way up the alabaster stairs of some ruined temple, a flashing sword in one hand and a scantily clad beauty lolling over his free arm.

The cover of the 1982 Cirith Ungol album King of the Dead. Like all Cirith Ungol albums, King of the Dead’s cover art features an illustration by Michael Whelan depicting Michael Moorcock’s sword and sorcery hero Elric of Melnibone.

He goes on to describe sword and sorcery in particular, espousing the view that “sword and sorcery novels and stories are tales of power for the powerless.” The sword and sorcery adherent, King writes, is “the fellow who is afraid of being rousted by those young punks who hang around his bus stop can go home at night and imagine himself wielding a sword, his potbelly miraculously gone, his slack muscles magically transmuted into those ‘iron thews’ which have been sung and storied in the pulps for the last fifty years.”

To be fair, I don’t particularly care for the “scantily clad beauty lolling over [the hero’s] free arm,” either, nor for the “prowess at fucking.” The banal plots and bland characterization aside, there is much to criticize in older sword and sorcery when it comes to depictions of women and race, particularly, which are often stereotyped to a high degree.

But to address King’s point, ironically I really was once someone who felt a “decided shortage of power.” I used to feel utterly powerless in life, shackled by chronic health issues. For years, I had constant pain in my hands and feet from a nebulous condition best described as small fiber neuropathy and fibromyalgia. It hurt to exercise, it hurt to write, even, at times.

During those years, however, I never was drawn to the heroes of sword and sorcery media. I didn’t care at all for the stereotypes and hackneyed narratives of these tales.

Now that I am physically competent, able to lift and run and climb with relative normalcy, I find myself increasingly drawn to the heroes without limits who inhabit the sword and sorcery realm.

Sure, I’m not some imposing, muscled figure like the swordsmen on the covers of the metal albums I listen to or fantasy novels I read, but I also don’t feel anything resembling a “shortage of power” in my own life.

If anything, I feel more powerful now than I ever have. It’s the opposite of what King hypothesizes.

But when I say I dig sword and sorcery heroes, don’t get the wrong idea. There’s a limit to how much of the stuff I can read. There’s a limit to how much anyone can read. Like I said before, it’s formulaic. You know exactly what’s going to happen, even often what the characters are going to say in response to various situations, 95 percent of the time.

It’s nauseating.

But it’s also calming.

It’s reassuring to know these stories of human beings with unlimited power. Because that’s what’s so great about the very best sword and sorcery.

It’s distinctly human.

It’s primal. The protagonists of old pulp school sword and sorcery, like Conan and Kull, are nothing but plain old humans. They often battle magic, but wield none themselves. They aren’t descended from kings or gods. They inherit no birthright. They aren’t bestowed with powers from otherworldly spirits or witches or age-old prophecies. They aren’t bitten by radioactive spiders and don’t fall into vats of toxic waste.

They live and fight like normal humans, but they always come through in the end (at least the main characters usually do… almost everyone else dies along the way).

The cover of Iron Kobra’s 2015 album Might & Magic depicts a typical example of a sword and sorcery narrative’s climax at play.

Their strength is attributed solely to skill and training, and in the case of Conan, arguably the best example of the archetypal sword and sorcery hero, their savage upbringing… In a sense, the fact that they’re strong is because they’re more in touch with their humanity than the civilized, domesticated characters around them.

Yeah, they’re one-sided and cliched, with boundless strength, stamina and skill, and a lack of any fear, but it’s how they got there that matters.

They represent the raw strength of unchecked human potential.

These characters live and die hard and fast. There are no chronic illnesses, no slow wasting away, no paralysis, no sucking applesauce through a straw while daytime television drones in the background, no scrolling endlessly through memes you do not remember thirty seconds later. Heads are cleaved open, guts are spilled. They are there and they are gone.

⸻

The night before I was supposed to finish this essay and publish it here, I had a nightmare.

In this nightmare, a vagrant walked into my house and stuck a piece of rebar into my chest, right below my armpit. I felt it going in slowly, deep into my chest cavity. The metal was very cold. I staggered back, trying to pull it out, moving in that strange, slow way of dreams, as though I was underwater or covered in molasses.

“You pull that out, you’ll bleed out in seconds,” the guy told me, grinning. He laughed ceaselessly, like a hyena, while I scrabbled around on the ground, writhing with the rebar sticking out of my chest.

I didn’t feel scared, in this dream, but I felt very weak. Unbelievably weak. I felt lower than a human being. I felt like a cockroach or spider, when you smash them with a wad of toilet paper but they’re not dead yet and they’re squirming feebly using a few of their working legs, trying to move nowhere in particular, and then you scoop them up and flush them down the toilet.

When I woke up, my chest was aching in the same spot the rebar was stuck into, and I started thinking about power again.

So I got up at 4:00 am and started trying to write this all down.

The more I think about it, the more I realize that my affection for sword and sorcery mimics many other experiences that bring me joy in life.

Riding motorcycles. Spending time in the mountains. Traveling and living alone.

The common line running through all these practices is that they seem to make me feel powerful. When I am going fast on a bike, standing on the top of a high place that I have climbed to, or in a place where no one knows my name or can understand my words… that’s when I feel the best about myself, not in reference to other people, but in reference to some ideal that sits in the back of my head about what a person should be.

Of course, much of that power is an illusion.

Sword and sorcery isn’t real, and neither is the power I feel on the back of a bike. One flick of the wrist, one semi-truck pulling out in front of me, one tire blowing out… I’m splattered. Gone.

It’s easy to sit there listening to heavy metal and doing pushups and think you’re tough as nails. It’s easy to go fast on a motorcycle and think that engine between your legs gives you power when it could also carry you to your doom at a moment’s notice. It’s easy to stand on the top of a mountain and think you run the world, then get hit by a storm a few seconds later and freeze to death.

I like to think I’m comfortable with death, and I’ve been in a handful of hairy situations, but I’ve never been on the brink of it. I’ve never had the rebar sticking out of my chest. That’s another thing entirely, I imagine.

The only situation that can compare is when I took a 100-foot-fall down the side of a mountain in Ecuador while climbing. I was sure I was going to die then, and I wasn’t particularly scared (again though, I felt weak), but I was just falling, there was nothing I could do one way or another.

Until those moments arrive, those moments when we have a choice, we don’t know what power we hold, or what we’ll do with it. Will we end up scrabbling on the floor like a roach?

I don’t know if I like sword and sorcery so much because it gives me the illusion of power, or the realization that we can all choose what to do with whatever power we do have as human beings, whether it’s boundless, like Conan’s, or limited, like yours and mine.

In my dream, I could see the vagrant coming up to the open front door from the window in the other room. I saw him holding this sharp piece of rebar, I could tell he was bad news, and I knew my friend’s girlfriend and my little sister were inside the house behind me. So I came at him.

At the end of the day, I reckon that’s all you can do, and consequently, it’s all that really matters.

Owen Clarke is a freelance writer, motorcyclist, and mountaineer, and the founder of this publication. You can find his work on his website.